A tribute to Yair Elmaleh z”l on his 1st Yahrzeit (speech given by Michelle Elmaleh)

B’chvod Harabannim, Ima and Abba, family, friends, talmidim and talmidot—

Thank you very much for joining us tonight to commemorate the first yarzheit of our dear brother and uncle, Yair ben Harav Chaim v’Yaffa. While it is hard for

Gil and I to believe that a year has gone by since Yair’s petirah, your support throughout this very difficult time has not gone unnoticed and for that we are very grateful.

Gil and I to believe that a year has gone by since Yair’s petirah, your support throughout this very difficult time has not gone unnoticed and for that we are very grateful.

For those of us who knew Yair well, and for those who never met him at all, allow me to share some of my thoughts about Yair and the reason we have chosen this venue to mark his first yarzheit tonight:

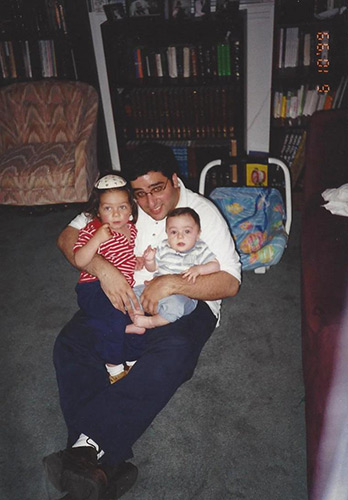

Yair was, amongst many things, a spirited, personable, endearing individual, whose life was cut short at the very young age of thirty-four. His innate generosity knew no bounds, as his friends, family, and specifically his nieces and nephews could attest to. Yair’s life, which he lived alone, was actually a life that he lived for others—those of us close to him know full well what he did to enhance our smachot, what he would do for us as friends, how he gave endlessly of his own time and money to be there for others.

Yair lived a life of chessed, which is often defined in our world as one who contributes to the major chesed organizations whose names we all know. And Yair certainly fit that bill—YUSSR, Camp Simcha, Yachad, Beis Ezra, Sinai Special Needs—to name just a few of the organizations that Yair volunteered for at various points in his life. But I don’t think that that is what made Yair unique, nor what continuously makes those who knew him associate Yair with the koach hanetinah that he inculcated so deeply into his being. For Yair’s life was largely defined by the small acts of kindness which, while we never took for granted, he raised the bar so high that we never lived up to his par either.

In thinking back to the last time I myself saw Yair, I am reminded that even this last encounter was one of Yair’s classic selfless moments, where all he wanted to do, quite subtly, was give. I was on my annual recruitment trip in NY and it was one of my last days in the States. At the end of a long day of interviews, I stopped off to buy myself some dinner and from there called Yair to tell him that I was

around the corner and was going to drop something off that Gil had sent with me. Perhaps two minutes later, when I got to his apartment, Yair was dressed, with his coat on, appearing as if he were going out. He said that he knew that I needed a quiet place to eat my dinner and unwind after a long day and since he was going out and wasn’t going to be home until late anyway, I should just stay in his apartment for as many hours as I wanted, and when I left, the door would lock behind me. But he didn’t just offer me his apartment—he actually insisted, pointing to the cable TV and the glass of ice he had already prepared for me on the table. I asked him if he was really on his way out or if he was just going out so that I would be able to use his apartment—I remember he claimed that he was offended that I could even think that he was making up a story. But that was Yair—he could have, and would have, made up a story—or many stories—in order to be able to help someone out. And it always came effortlessly to Yair. And to this day I do not know if Yair was really on his way out of his apartment, or if he was leaving just to be able to allow me to have a place of my own for a few hours. Typical Yair.

While Yair did many acts of chessed that  noone ever knew about, most often Yair’s generosity was hard to miss. He didn’t just bring balloons to Shmoobie’s shalom zachor, he brought two dozen—one of which was so large that it barely fit into his little green Saturn. Yair didn’t just dance at his friends’ weddings—he spent hours of his time and many of his dollars, planning out personal shtick to perform in the center of the circle. Yair didn’t bring chocolate to my parents’ house when he joined us for pesach—he brought a tray of chocolate that took close to a year to finish. If he joined you for a meal on Shabbat, he didn’t bring you one dessert—he brought you four, even if there were only three people at the meal. This was Yair—generous at his core, putting others before himself.

noone ever knew about, most often Yair’s generosity was hard to miss. He didn’t just bring balloons to Shmoobie’s shalom zachor, he brought two dozen—one of which was so large that it barely fit into his little green Saturn. Yair didn’t just dance at his friends’ weddings—he spent hours of his time and many of his dollars, planning out personal shtick to perform in the center of the circle. Yair didn’t bring chocolate to my parents’ house when he joined us for pesach—he brought a tray of chocolate that took close to a year to finish. If he joined you for a meal on Shabbat, he didn’t bring you one dessert—he brought you four, even if there were only three people at the meal. This was Yair—generous at his core, putting others before himself.

I do not claim to know what drove Yair to be such a giver. I don’t know if it made him feel good about himself, if he thought it was the moral thing to do, if his desire to give was religiously driven. I never had the opportunity to ask him. But I do know that now I often find myself in situations where I do things that I would never have done before, and in my head, I say “that was for you, Yair.” A disabled young woman was on line in front of me at the supermarket and she didn’t have enough money to pay for her purchases. I gave her the money and banked a random act of chessed, only because Yair would have done the same. I held the door open for a very slow moving elderly woman during the summer and when she finally reached the door and realized I had been holding it for her, she gave me a bracha—that one was for Yair too. At moments like these I think to myself, I don’t do these kinds of things. But now I do, because Yair did. Not surprisingly, immediately after Yair’s petirah, my talmidot organized a campaign l’ilui nishmat Yair in which they collectively did and recorded random acts of kindness, and then sent them to me and Gil as a chessed log. There could be no greater tribute to the memory of Yair Elmaleh than to increase one’s acts of selflessness on a day to day basis—that is who Yair was, that is what his essence imbued.

Yair was a presence—in his life, if he walked into a room, you knew he was there. If you met him even for a brief moment, he wasn’t the type you would forget easily. In many ways, his presence lingers, even after his death. In my home, the beloved Uncle Ya-Ya has not been forgotten. My kids guard what they now have that was once his—the last 5 dollar bill that Yair sent to Shmoobie in the mail along with the loving note that accompanied it, are framed and hanging over Shmoobie’s bed. On motzei Shabbat, the kids fight over who gets to use the basamim holders which we saved as a memory from Uncle Ya-Ya’s apartment. Hila asks many questions about death, which always refer to Uncle Ya-Ya in shamayim. Even Bat-Zion, at the age of two, can pick Uncle Ya-Ya out of a picture and speaks of him as if he is a part of her life.

Somehow, Yair left his mark—on our family, on his friends, and, I am pretty sure, on all who knew him. It is for this reason that Gil and I spent many long hours, agonizing over what we could do—both for Yair’s first yarzheit, and also for the long term—to properly memorialize Yair and to capture the essence of his existence. It seemed that every idea we had, Yair could have executed better. We thought “big”—in true Yair fashion—and many of our ideas, which for now are on the back burner, required much more money, resources, and energy than are currently available to us. We hope that Yair Le’olam, the fund that Gil established immediately after Yair’s petirah will one day be expansive enough to fund some of the bigger dreams that we hope to fulfill in Yair’s memory as time goes on, B”H.

For the here and now, in order to mark the first yarzheit of Yair’s petirah, Gil and I are happy to announce a new initiative that we have started in conjunction with L’ma’an Achai, here in Ramat Beit Shemesh, which will be called Chessed Yair L’olam. This project involves school visitations, conducted by the trained staff of L’maan Achai, which will educate school-aged children about living a life of chessed and how to take advantage of the multitude of chessed opportunities around t

hem. We could think of no better way to capture the life of chessed that Yair lived than by giving young children the opportunity to start thinking about the midah of giving from a very young age. The hope, of course, is that those  children who are exposed to this new program will ultimately incorporate the value of chessed into their lives and will continue to actualize this value all the way through into their adult lives as well.

children who are exposed to this new program will ultimately incorporate the value of chessed into their lives and will continue to actualize this value all the way through into their adult lives as well.

Gil and I also felt it to be very important that we use Yair’s yarzheit each and every year as an opportunity to have those who knew Yair take a look at life from a similar perspective to Yair’s—to take the opportunity to evaluate our own standing in terms of our power to give—something I believe that Yair didn’t spend too much time doing since giving was not something he thought about, it was something that simply he did. To that end we decided to initiate an annual shiur, which will B”H address the topic of chessed—from the theoretical to the practical—which tonight will be given by Rav Judah Mischel, maggid shiur at both the Reishit Yeshiva and HASC.

While Rav Judah, a personal friend of Gil’s, was kind enough to help us get our initiative off the ground, he also expressed hesitancy at the idea of speaking at an azkara for someone whom he never met personally. We reassured him that we could think of noone better for the job—since Rav Judah’s essence—his capacity to live his life for others, particularly his talmidim, would have been a point of commonality that he would have shared with Yair had their paths ever crossed. It is an honor for us that Rav Judah will be delivering the first annual shiur l’ilui nishmat Yair ben Harav Chaim v’Yaffa.